The Hidden Cost of Trashing Vegetables

How tossing your banana peels in the garbage is costing you, and your planet, in more ways than you think.

The Problem

According to the EPA, one in every two items thrown in a U.S. trashcan is compostable, and a quarter of every landfill is comprised of food waste. In fact, in the U.S. just 5% of compostable materials are properly disposed of, while more than 90% end up in municipal landfills. Of course, this disparity leads to lower property values for locals and a deleterious environmental impacts in neighboring regions, but tossing your banana in the garbage doesn’t just affect the trash heap you send it to, it touches every corner of the world.

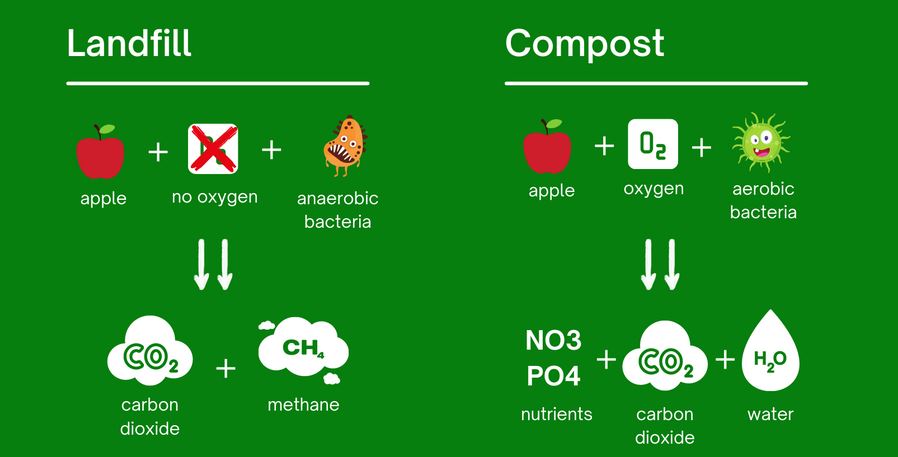

In a healthy ecosystem, bacteria combine the carbon and hydrogen trapped in organic matter with oxygen gas to create water and carbon dioxide. It also produces valuable nutrients, including nitrates and phosphates, that are essential for plant growth. And if that wasn’t enough, this reaction often generates enough heat to kill most pathogens, including Salmonella, E. Coli, and fungi, making its products safe for plants, humans, and the environment alike.

However, matter buried within a landfill lacks a consistent oxygen source, forcing it to decompose anaerobically (without oxygen). This process takes longer, smells worse, is less likely to kill harmful pathogens, and produces large amounts of methane, a greenhouse gas more than 27 times more potent than carbon dioxide. Moreover, there is no economic way to retrieve the compost itself, effectively neutering the process’ only remaining benefit. All for the sake of convenience.

And the impact of this convenience is far from trivial. Landfills alone represent more than 17% of all methane emissions and 3% of all greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S. That’s the equivalent of 50 MILLION cars and carries an estimated annual tab of about $8 BILLION. And while gas collection systems are improving, more than 60% of landfill methane continues to end up in our atmosphere.

The Solution

So what can you do? Well, for starters, compost. If you have a yard, invest in a larger compost bin. If you don’t, or your HOA won’t allow a larger bin, think about buying a countertop bin or an electric composter. More importantly, however, support local compost initiatives, such as curbside pickup, community partnerships, and educational programs. The easier it is for people in your community to compost, and the more they understand its benefits, the bigger the impact will be.

But not all compost is create equal, nor is every locale equally equipped to manage large-scale compost streams. Animal byproducts can smell, weeds can spread, and ‘compostable’ utensils are difficult to break down. These materials require specialized facilities to decompose properly. And for 12% of U.S. households, these facilities will pick-up right from your doorstep. For the rest of us, we either have to transport our rotting food waste ourselves or, more often, throw it away. So be sure to do your research, see if there’s a facility near you, and advocate for municipal pickup and processing whenever possible.

Finally, when it comes to composting, current materials, technologies, and services have not yet risen to meet the moment. But they are close. Companies like CompostNow, Bootstrap Compost, and Compost Crew provide regional residential and commercial pick-up services. Nutritower, Sepura, and BioHiTech Global provide on-site solutions for aspiring composters of all sizes. And Intropic Materials, Mango Materials, and Cruz Foam are engineering compostable alternatives to popular consumer goods. Each of these companies make composting easier, and supporting them and others will be an imperative step in bringing composting into the mainstream.

For every ton of food waste that reaches a landfill, 0.86 tons (0.78 metric tons) of carbon dioxide equivalent escapes into our atmosphere and, as of right now, we have no way to capture it once its out there. But there is still hope. Unlike carbon dioxide, which can linger for centuries, methane only lasts about 12 years. That means that actions we take today could have a huge impact on the environment in the short-term. So let’s work together to make sure our banana peels and egg shells feed farmlands instead of landfills.